BY JEFFREY A. TUCKER JUNE 4, 2022 LIC

Americans have limitless faith in democracy. In the early 19th century, that charmed Alexis de Tocqueville. His book Democracy in America still rings true today because not much has changed. The entire country can be in ruins and even then, most people figure that it will all be improved or even solved come November. It’s been going on for our entire history. As a people, we believe our elections are what keep the people and not the dictators in charge.

Surely some of this faith is necessary simply because it is the only option we have. The sitting president and his party are in deep trouble now, and most observers are predicting a rout in the midterm elections, granting us two additional painful years of inflation plus recession unfolding amidst what will surely be a brutal political stalemate and cultural upheaval. Then November will come again and with it another round of trust that the new president will figure something out.

This faith in our elected leaders is belied by the experiences of the last 30 months. To be sure, the elected politicians are nowhere near blameless in what unfolded and they could have done far more to stop the disaster. Trump could have sent Fauci and Birx packing (maybe?), the Republicans could have voted no on trillions in spending (did they really have a choice?), and Biden could have renormalized the country (why didn’t he?). Instead they all went along…with what? With advisers from the bureaucracies, the people who have de facto ran the country for this entire grim period.

Reading Scott Atlas’s book, one comes away with a very strange picture of how Washington worked in the first year of the pandemic. Once Trump gave the green light to lockdowns, the permanent bureaucracy had all it needed. In fact, this happened even before Trump approved it: the Department of Health and Human Services had already released its lockdown blueprint on March 13, 2020, a document which had already been weeks in the preparation. After the March 16 press conference, there was no going back. The “deep state” – by which I mean the permanent non-appointed bureaucracy and the pressure groups to which it answers – was running the show.

The administrative state has probably not enjoyed such a good run since World War II or perhaps much earlier if ever. These were certainly the salad days. Merely by assigning a bureaucrat to type on a screen, the CDC could cause every retail business in the US to install plexiglass, force people to stand 6-feet apart, make the human face publicly invisible, close or open whole industries at will, and even scrap religious services and singing. To be sure, these were mere “recommendations” but states, cities, and corporations deferred for fear of liability should something go wrong. The CDC provided the cover but acted pretty much like a dictator.

We know this for certain given the CDC’s response to the Florida’s judge’s decision to declare the transportation mask mandate illegal. The response was not that the mandate was both compliant with the law and necessary for public health. Instead, the agency and the Biden administration too rallied around a simple point: the judge’s decision cannot stand because courts should have no authority to override the bureaucracy. They actually said it: they demand total, unchecked, unquestioned power. Period.

This is alarming enough but it speaks to a much larger problem: a hegemonic bureaucratic class that is not controlled by the political class and believes that it possesses total power. The implications extend far beyond the CDC. It applies to every executive agency of the federal government. They ostensibly operate under the authority of the office of the president but actually not even that is true. There are severe restrictions in place on the ability of the elected president to fire anyone among them.

Trump couldn’t fire Fauci, at least not easily, and he was told this repeatedly. That pertains to millions of other employees in this category. This was not the traditional American system. In the days before 1880, it was routine for new administrations to toss out the old and bring in the new, and yes of course that included cronies.

That system came to be derided as the “spoils system” and it was replaced by the administrative state with the Pendleton Act of 1883. This new law was passed in response to the assassination of President James Garfield. The culprit was an angry job seeker who had been rebuffed. The supposed fix, backed by Garfield’s successor Chester A. Arthur, was to create a permanent civil service, thus supposedly reducing the incentive to shoot the president. It initially pertained to only 10% of the federal workforce, but it had developed vast power by the time of the Great War.

It wasn’t until I read Alex Washburne’s piece on Brownstone that the full implications became obvious to me. He cites the existence of something called the Chevron doctrine of deference to the agency. Whenever there is a question of an agency’s interpretation of the law, the court should defer to the agency and not to a strict reading of the law. Getting curious about this, I clicked through to the Wikipedia entry on the topic.

Here is where we find the amazing revelation: this egregious rule came about only in 1984! The case in question was Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. and the issue concerned the EPA’s interpretation of a Congressional statute. John Paul Stevens wrote in the majority opinion:

“First, always, is the question whether Congress has directly spoken to the precise question at issue. If the intent of Congress is clear, that is the end of the matter; for the court, as well as the agency, must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress. If, however, the court determines Congress has not directly addressed the precise question at issue, the court does not simply impose its own construction on the statute . . . Rather, if the statute is silent or ambiguous with respect to the specific issue, the question for the court is whether the agency’s answer is based on a permissible construction of the statute.

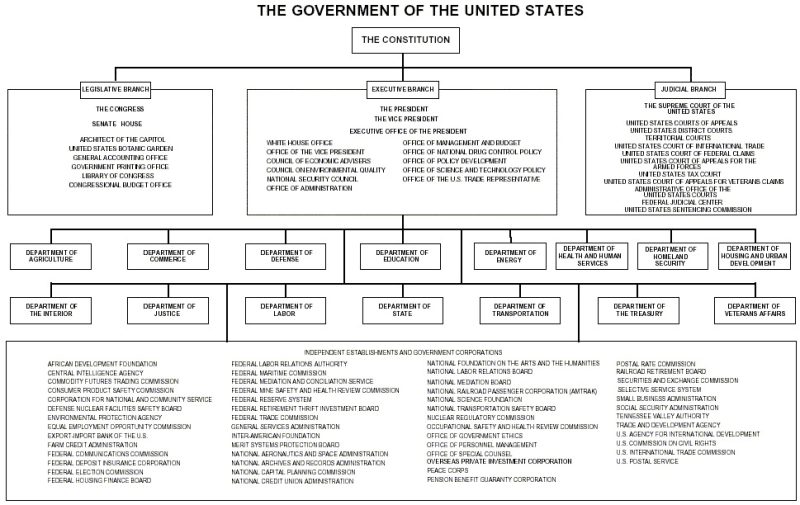

All of this begs the question of what is permissible, but the critical thing is the dramatic shift in the burden of proof. A plaintiff against an agency must now demonstrate that the agency’s interpretation is impermissible. In practice, this rule has granted tremendous latitude and power to executive agencies to rule the whole system with or without political permission.And keep in mind what this chart looks like:

The lower two-thirds of this chart is increasingly the government as we know it, and its power is unaccountable to the president, to Congress, to the courts, or to the voters. From what we know about the operations of the FDA, DOL, CDC, HHS, DHS, DOT, DOE, HUD, FED, and so on throughout every combination of letters you can think of, is that they are typically captured by private interests powerful enough to buy themselves influence, complete with revolving doors in and out.

This creates a governing cartel that is a formidable force against democracy and freedom itself. This is a major and highly significant problem. It’s not clear that Congress can do anything about it. Worse, it’s not clear that any president or any court can really do anything about it, at least not without facing a barrage of brutal opposition, as Trump learned first hand.

The administrative state is THE government. Elections? They provide just enough difference to lead people to believe they are in charge, but are they? Not according to the organization chart. This is the real problem with the US system today. This system cannot be found in the US Constitution. No one alive voted for it. It just gradually evolved – metastasized – over time. The last 30 months have demonstrated that it is a real cancer eating out the heart of the American experience, and not just here: every country in the world deals with some version of this problem.

Americans’ romance with democracy continues unabated and right now, everyone I know is living for the great day in November when the existing crop of elected leaders can be shown a thing or two. Good. Throw the bums out. The question is: what should the new class of elected leaders do about this much deeper problem? Can they do anything about it even if they had the will?

Keep in mind that it pertains not just to the public-health bureaucracies but to every aspect of public life in America. It’s going to take far more than a few elections to fix this. It is going to require focus and public support for a restoration of a genuine constitutional system in which the people rule with their elected leaders as their representatives, without the vast meta-layer of state control that pays no attention to the comings and goings of the elected class.

In sum, the problems are much deeper than most people realize. These problems have been on display for the public in these past two-plus years. During this time, American life as we knew it was upended by an unaccountable administrative bureaucracy – in Washington but with reach into every state and city – that ignored the Constitution, evidence, public opinion, the pronouncements of elected leaders, and even the courts.

Instead, this machinery of coercion ruled in concert with a network of private-sector actors, including media and financial companies, that have outsized influence and routinely use these agencies as weapons in their own economic interests at the expense of everyone else.

This system is indefensible. Experiencing it first hand in the 1950s, Dwight Eisenhower decried the entire machine in his farewell address of 1961. He warned of the “danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.” It is the task of statesmanship, he said, to uphold “the principles of our democratic system – ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.”

Uprooting the entrenched, arrogant, hegemonic, and unaccountable administrative state that believes it operates with no limit to its power is the great challenge of our time. The public is probably nowhere near aware of the full extent of the problem. Until voters themselves figure it out, the politicians will have no mandate even to test a solution.